Building a Toy Database: Concurrency is Hard

Hey folks, it's been a while. Here's some news on Bazoola, my precious toy database, which already reached version 0.0.7!

Demo App

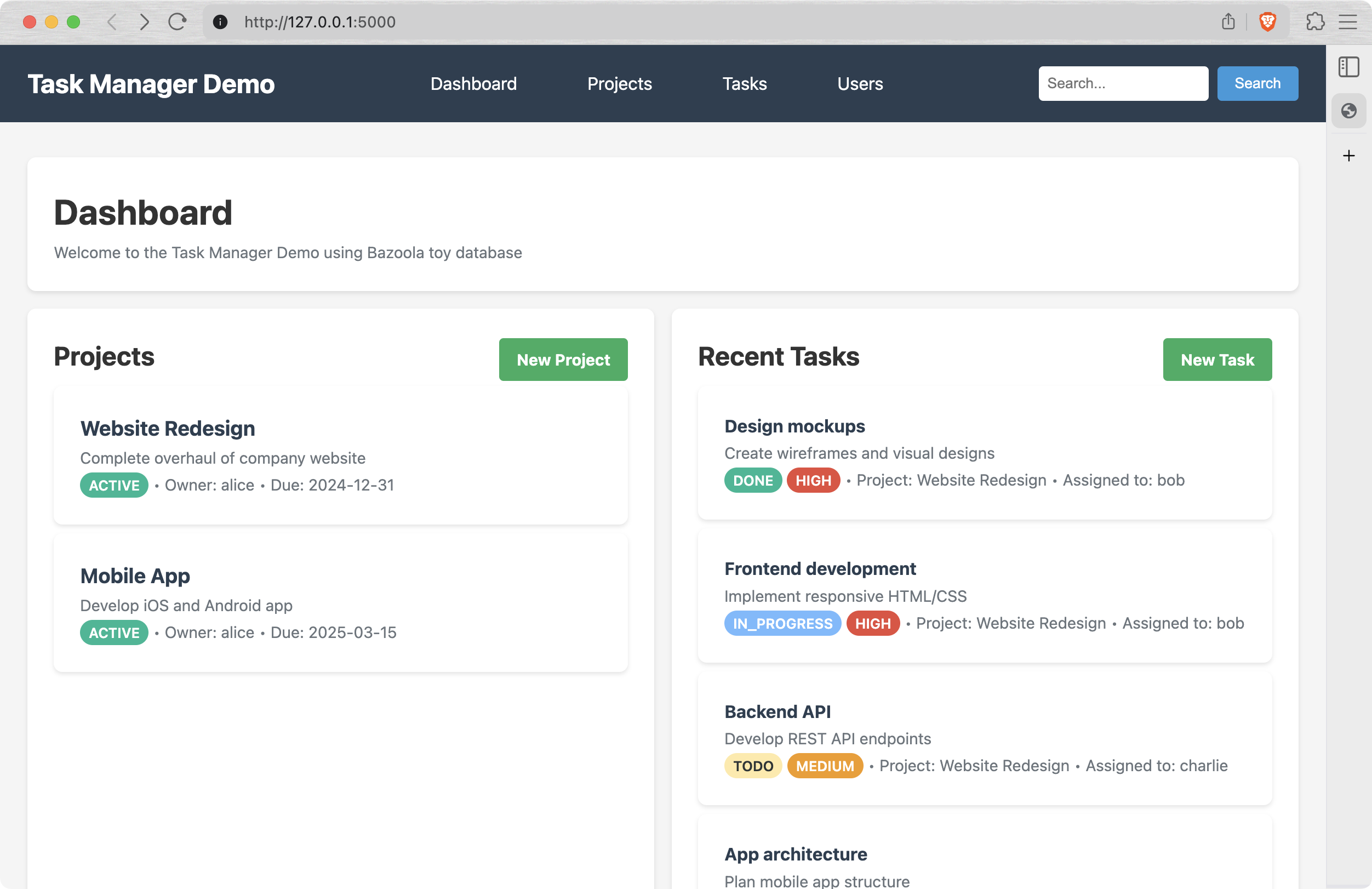

Meet the "Task manager" - a flask-based app demonstrating current capabilities of Bazoola:

In order to run the task manager:

git clone https://github.com/ddoroshev/bazoola.git

cd bazoola

pip install bazoola

python demo/app.py

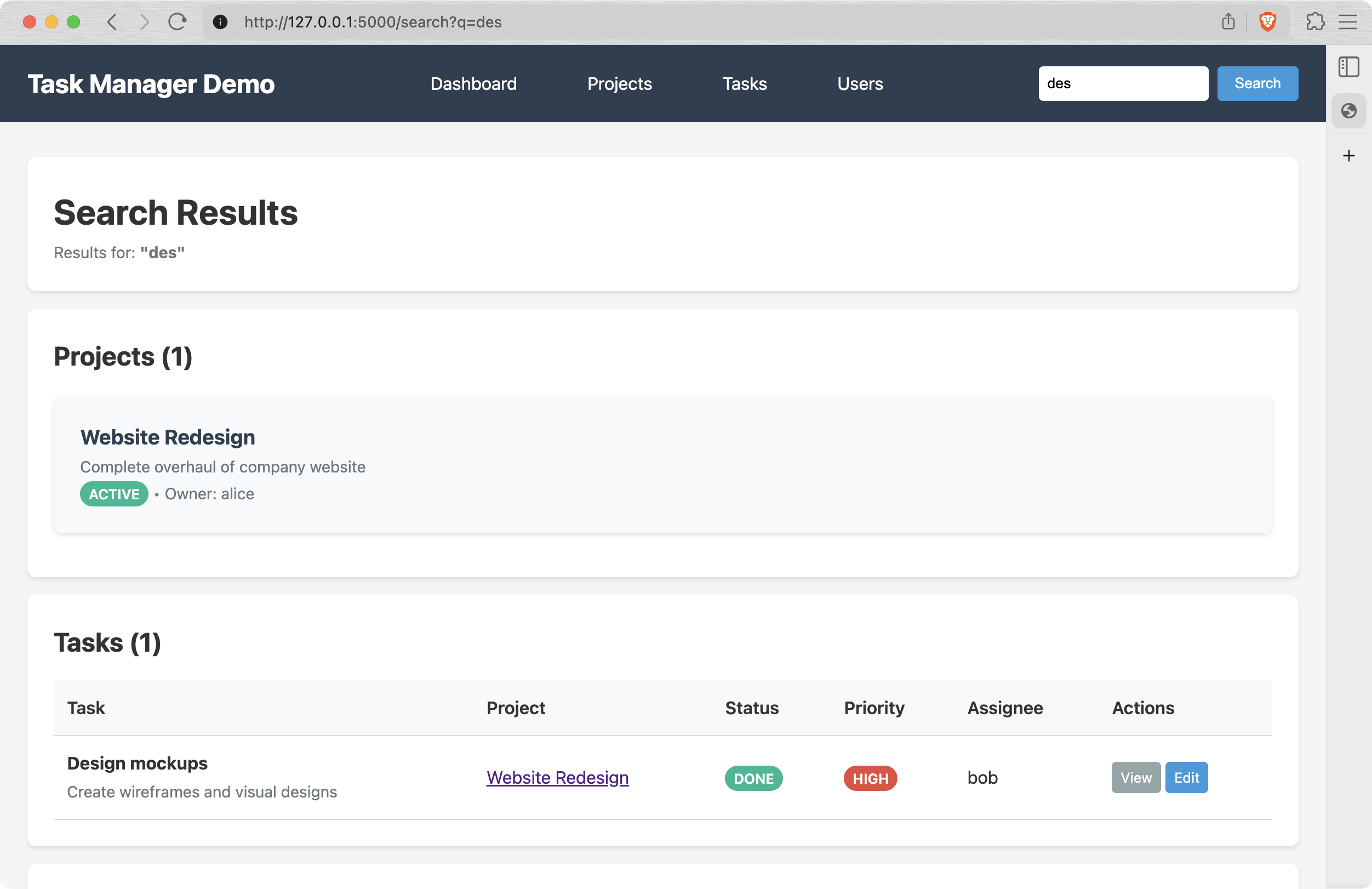

Then open http://127.0.0.1:5000 in your browser, and Bob's your uncle. The schemas and tables are all pre-created and filled with demo data, so you can browse and edit it, checking the explanation at the bottom of the page. For example, you can try to search design-related projects and tasks by "des" query:

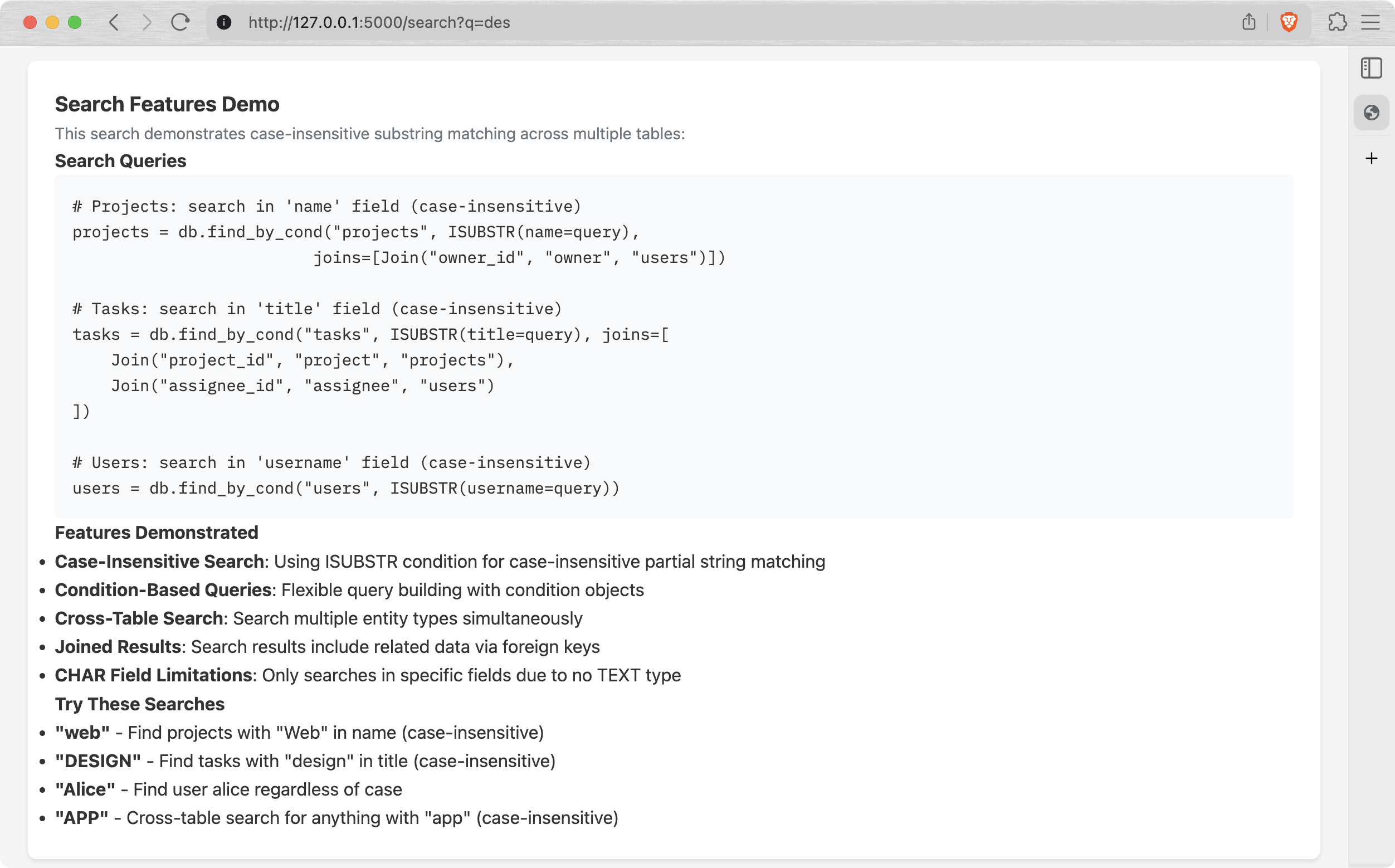

If you scroll down a bit, there's an explanation of how it actually works:

I'm still working on the TEXT field implementation, so for now all descriptions and comments are basically CHAR(200), but this will change soon.

Also, cherry on top - this demo app has been almost entirely generated by ✨Claude Code! That was a huge boost for me, because it helped focus on the essentials, delegating the boring stuff to AI.

Concurrency

Finally, this thing can be run in concurrent environment: in parallel threads or even in parallel processes. There are no parallel operations though, but at least the data won't corrupt if you run two apps using the same data directory simultaneously.

The key is a global lock. In a nutshell:

class DB:

# ...

def insert(self, table_name, values):

with self.storage.lock():

# ...

return tbl.insert(values)

def find_all(self, table_name, *, joins=None):

# ...

with self.storage.lock():

rows = self.tables[table_name].find_all()

# ...

return rows

def find_by_id(self, table_name, pk, *, joins=None):

# ...

with self.storage.lock():

row = self.tables[table_name].find_by_id(pk)

# ...

return row

def delete_by_id(self, table_name, pk):

with self.storage.lock():

self.tables[table_name].delete_by_id(pk)

def update_by_id(self, table_name, pk, values):

with self.storage.lock():

# ...

return self.tables[table_name].update_by_id(pk, values)

Actually, there are two global locks under the hood:

- A

.lockfile, essentially a global mutex shared between the processes via flock. - A

threading.RLockobject, shared between threads of a single process. However,flockis not enough, because it's basically useless within the same process.

# storage.py

class File:

# ...

@contextmanager

def lock(self):

try:

fcntl.flock(self.f.fileno(), fcntl.LOCK_EX)

yield

finally:

fcntl.flock(self.f.fileno(), fcntl.LOCK_UN)

# ...

class TableStorage:

def __init__(self, cls_tables, base_dir: str):

# ...

self._threadlock = threading.RLock()

self._lockfile = File.open(".lock", base_dir=base_dir)

# ...

@contextmanager

def lock(self):

with self._threadlock, self._lockfile.lock():

yield

It's not about atomicity, it doesn't solve data consistency in general, i.e. if you unplug your computer in the middle of a write operation, you'll most likely lose some ¯_(ツ)_/¯

Elimination of find_by and find_by_substr

Initially, I had two specific functions:

find_by(table_name, field_name, value)- an equivalent ofWHERE field_name == valuefind_by_substr(table_name, field_name, substr)-WHERE field_name LIKE substr

However, there's already find_by_cond(), allowing to search by arbitrary conditions, defined in cond.py.

So I just added EQ, SUBSTR and ISUBSTR and removed these two helpers in favor of find_by_cond(table_name, EQ(field=value)) and find_by_cond(table_name, SUBSTR(field=substr)).

One More Thing

One of the features of this database at the moment is it's size - its core implementation is less than 800 lines of Python code! I decided that it would be nice to highlight it in the Github description, and came up with a simple script, update_description.sh, which I run once in a while to count the lines of bazoola/*.py and update the repo description.

I didn't find out yet how to run it on CI, but I think this one is already good enough.

Conclusion

I treat this update as a huge leap: a month ago Bazoola was barely usable in real-life applications, and now you can build something on top of it. There's no VARCHAR or TEXT fields, the amount of conditions (EQ, LT, GT, ...) is quite limited, selecting particular fields and ordering is also not implemented, and that's why it's just a 0.0.7 release :)

I like the fact that the data files contain mostly plain text, it's easy to test and debug the logic and data consistency. Of course, I'm planning to go binary and to switch from Python to C, and those benefits disappear, but by that time I'll have a solid amount of tests and a bunch of tools for managing the data.

Stay tuned!

Building a Toy Database: Learning by Doing

Ever wondered how databases work under the hood? I decided to find out by building one from scratch. Meet Bazoola - a simple file-based database written in pure Python.

Why Build a Toy Database?

As a developer, I use relational databases every day, but I never truly understood what happens when I INSERT or SELECT. Building a database from scratch taught me more about data structures, file I/O, and system design than any tutorial ever could.

Plus, it's fun to implement something that seems like magic!

What is Bazoola?

Bazoola is a lightweight, educational database that stores data in human-readable text files. It's not meant to replace SQLite or PostgreSQL - it's meant to help understand how databases work.

Key Features:

- Fixed-width column storage

- CRUD operations - the basics every database needs

- Foreign keys - because relationships matter

- Automatic space management - reuses deleted record space

- Human-readable files - you can literally

catyour data

The Core Idea: Fixed-Width Records

Unlike CSV files where records have variable length, Bazoola uses fixed-width fields:

1 Alice 25

2 Bob 30

3 Charlie 35

This makes it trivial to:

- Jump to any record by calculating its offset

- Update records in-place without rewriting the file

- Build simple indexes

Show Me the Code!

Here's how you use Bazoola:

from bazoola import *

# Define schemas

class TableAuthors(Table):

name = "authors"

schema = Schema([

Field("id", PK()),

Field("name", CHAR(20)),

])

class TableBooks(Table):

name = "books"

schema = Schema([

Field("id", PK()),

Field("title", CHAR(20)),

Field("author_id", FK("authors")),

Field("year", INT(null=True)),

])

# Create database instance and the files in `data/` subdir

db = DB([TableAuthors, TableBooks])

# Insert data

author = db.insert("authors", {"name": "John Doe"})

book = db.insert("books", {

"title": "My Book",

"author_id": author["id"],

"year": 2024

})

# Query with joins

book_with_author = db.find_by_id(

"books",

book["id"],

joins=[Join("author_id", "author", "authors")]

)

print(book_with_author)

# Output: {'id': 1, 'title': 'My Book',

# 'author_id': 1, 'year': 2024,

# 'author': {'id': 1, 'name': 'John Doe'}}

# Close the database

db.close()

Interesting Implementation Details

Space Management

When you delete a record, Bazoola fills it out with * symbols, maintaining a stack of free positions:

class Table:

# ...

def delete_by_id(self, pk: int) -> None:

# ...

self.f.seek(rownum * self.row_size)

self.rownum_index.set(pk - 1, None)

self.f.write(b"*" * (self.row_size - 1) + b"\n")

self.free_rownums.push(rownum)

# ...

def seek_insert(self) -> None:

rownum = self.free_rownums.pop()

if rownum is not None:

self.f.seek(rownum * self.row_size)

return

self.f.seek(0, os.SEEK_END)

This simple approach prevents the database from growing indefinitely.

Indexing

Every table automatically gets an index on its primary key in <table_name>__id.idx.dat file, so finding a record by ID is O(1) - just look up the position and seek!

Foreign Keys

Bazoola supports relationships between tables and joins:

# Query with joins

rows = db.find_all("books", joins=[

Join("author_id", "author", "authors")

])

# Inverse joins (one-to-many)

author = db.find_by_id("authors", 1, joins=[

InverseJoin("author_id", "books", "books")

])

However, it doesn't enforce referencial integrity yet, and you can basically delete anything you want ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Human-Readable Storage

Data files are just formatted text:

$ cat data/books.dat

1 My Book 1 2024

************************************

3 My Book3 1 2024

Great for debugging and understanding what's happening!

What I Learned

- Data format and file-based storages are tricky, that's why it's all just test-based.

- Fixed-width has trade-offs - simple implementation, but wastes space. Real databases use more sophisticated formats.

- Indexes are magic: the difference between O(n) table scan and O(1) index lookup is massive, even with small datasets.

- Joins are hard.

- Testing is crucial. Database bugs can corrupt data, and comprehensive tests saved me many times.

Limitations (and why they're OK)

The current implementation is intentionally simple:

- no transactions (what if it fails mid-write?)

- no concurrency (single-threaded only)

- no query optimizer (every operation is naive)

- no B-tree indices (just a simple index for primary keys)

- no SQL (just Python API)

- fixed-width wastes space These aren't bugs - they're learning opportunities! Each limitation is a rabbit hole to explore.

Try It Yourself!

pip install bazoola

The code is on GitHub. It's ~700 lines of Python (db.py) - small enough to read in one sitting!

What's Next?

Building Bazoola opened my eyes to database internals. Some ideas for further versions:

TEXTfields with a separate storage- strict foreign key constrainsts

- unique constraints

- B-tree indexes for range queries

ALTER TABLE- simple query planner

- pure C implementation with Python bindings

But honestly, even this simple version taught me a ton.

Conclusion

Building a toy database is one of the best learning projects I've done. It's complex enough to be challenging but simple enough to finish. You'll understand your "real" database better, and you might even have fun!